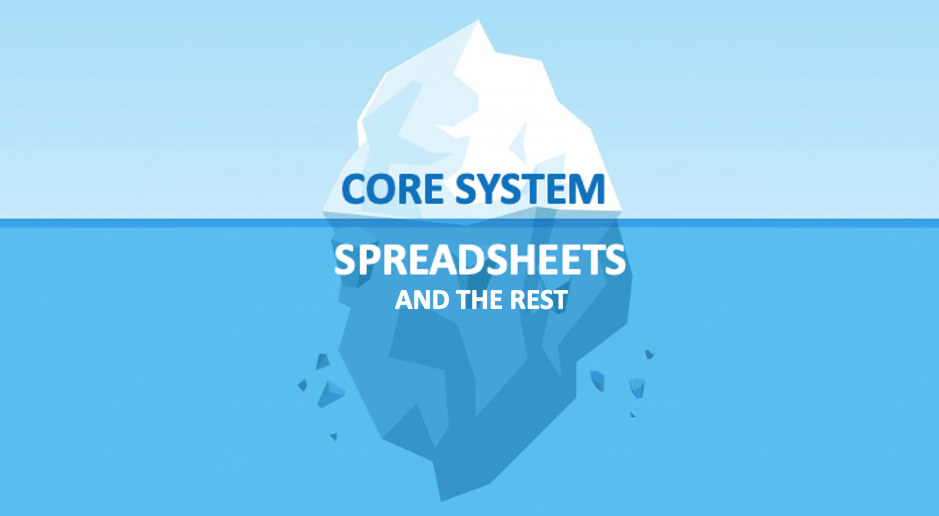

In a large organisation, for every core system (e.g.: HR, Finance, Operations, Sales) you will find a hundred spreadsheets. Is it bad?

Let’s start with a simple yardstick, devised from personal experience:

The Rule of One

A spreadsheet – the Swiss Army knife of tech – is perfectly fine when one person creates, maintains and is accountable for it.

When a spreadsheet is shared, it is meaningful only to the extent that you trust its owner.

“Many” and “spreadsheet” don’t go together: a personal tool can never be a system.

The Rule of One is easily breached: in any but the smallest of organisations, many people need technology to interact in many ways. Here are two of the most common examples where alarm bells should ring:

- data collection from many contributors: who hasn’t received an email with a spreadsheet template attached and the request “please fill out and send back by Friday at the latest”? It’s probably ok as a one-off… however, when many people are required to contribute, it is the enemy of efficiency, accuracy, traceability, accountability and should not become routine;

- using spreadsheets as a bridge between two systems, for data mapping and transformation: here, one could argue that a few clever macros could save weeks of development whilst maintaining degrees of freedom and flexibility… Yet, this would clearly be the weakest link in the chain, with people needing to carry out procedures particularly sensitive to human error for many iterations (weekly, monthly, …).

Breaching the Rule of One opens the flood-gates of Hidden Tech.

And the rest

I see Hidden Tech as anything that falls below the radar – the stuff that would not appear in an “official catalogue” of your organisation’s technology (but without which many processes would grind to a halt).

Spreadsheets have the peculiar characteristic of often being used “as systems” whilst not officially being recognised as such; to them, I would add “end-user applications” and “decaying tech”.

End-user applications are, for all intents and purposes, equivalent to “spreadsheet systems”: whatever software is used, it is inextricably tied to its creator – cue a consultant or graduate who applies their wizardry to rationalise and automate as quickly and effectively as they move on.

Decaying Tech is more subtle: yesterday’s great system, if not adequately invested-in over time, will become less and less visible, less understandable in terms of its inner-workings.

Is it bad?

The sheer volume of Hidden Tech you would normally find in any large, successful organisation suggests that there is something positive and / or inevitable about it.

Tools like spreadsheets can empower individuals – surely a good thing – and it’s important to remember that …

…for the most part, this stuff …works!

… Until it doesn’t.

The more you rely on anything you do not fully understand or control, the more fragile you become.

Why does it matter?

Ignoring Hidden Tech is like navigating blind or accepting a black-market economy.

In a mature industry, auditors will be quick to pick-up on significant breaches; the careless and the lazy will edge between the thrill of risking high-impact errors and the threat of closure by the Regulator (there is a rich online literature on disastrous spreadsheet errors).

How to fix it

The primary problem lies in the word “hidden” and the first step is to bring everything in plain view.

This is as easy as creating an up-to-date inventory of all systems, with a clear ownership structure where, in most cases, end-user tools will require a transfer of ownership away from the business and into the Technology Department.

Technology managers will then carry out the necessary assessments on security, accuracy, maintainability, costs vis-à-vis the expected benefits, officially recognising technical debt and planning the next steps accordingly.

Even though the technical debt due to spreadsheets, end-user tools, decaying tech – when fully brought to light – can be overwhelming, it will ultimately be just a long list where each item will end-up in one of three categories:

- ditch (costs/risks outweigh benefits)

- accept the risk (e.g.: non-critical, low frequency, low effort, easy maintenance)

- replace

Replacement will trigger the “build vs buy” dilemma.

Build vs Buy, chore vs opportunity

The very nature of what needs to be replaced, i.e.: the end user’s “original artefact” or an obsolete piece of tech, would suggest that we are in “build” territory: Hidden Tech is often born as a “local add-on” to a core system where, for whatever reason, it was not possible to integrate the functionality or because there was no product.

However, Hidden Tech often arises because the Technology Department does not have the capacity to deal with the sprawling landscape of user needs. To suddenly inherit ownership and build robust alternatives can be a big (if not impossible) chore.

On the other hand, an external vendor will see a big opportunity… here’s a chance to make a difference for a customer! In this light, the “buy” option could be a win-win, a way for the Technology Department to solve a problem while exploring new technology from the outside world.

It is also the case that the “artefacts” are not always that original and products do exist; also, that some Tech companies are entirely geared to assist with this kind of technology upgrades.

In the end, considering the nature, the variety and number of items to deal with, the best balance will probably be achieved somewhere in the middle.